The most important aspect of democracy is being able to vote for who represents you in government. Without that ability, democracy gives way to less accountable forms of governance. However, this core part of democracy is also one that can come in many different ways, each of which can drastically impact how candidates run their campaigns.

Ranked choice voting (RCV) is one such way that has been gaining a lot of traction in recent years. In comparison to the current “first-past-the-post” system, in which each vote is cast once and the candidate who gets a plurality of the votes (or in America, over 50%) wins, RCV presents an alternative method of choosing leaders.

Recently, it has received a lot of attention via its use in New York City’s mayoral election, in which the previously unknown democratic socialist Zohran Mamdani managed to pull off a surprise upset of former NY governor Andrew Cuomo alongside a wide range of other candidates. But there are certain quirks and outcomes of that election that are worth diving into.

Analysis

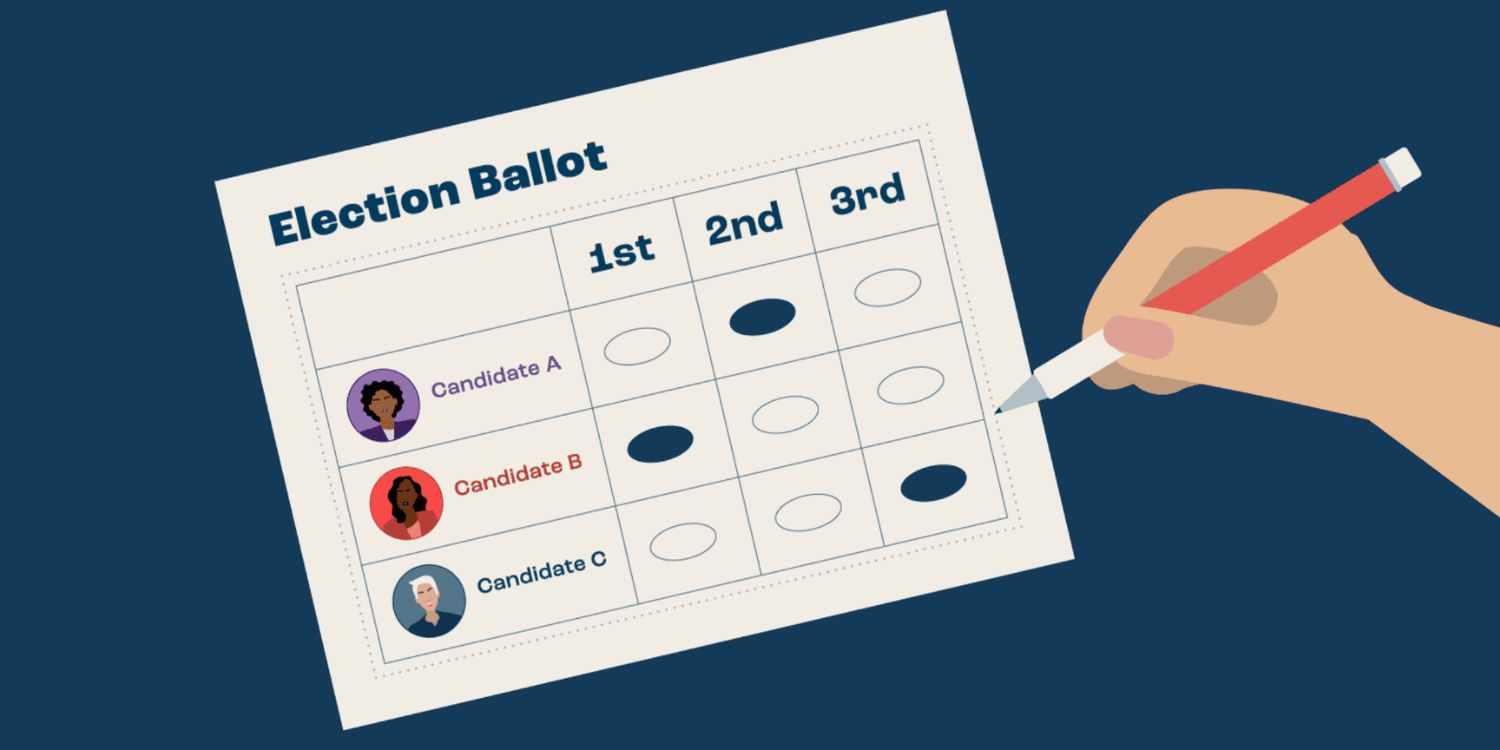

First, it is important to look at how RCV actually works. Instead of simply choosing to vote for one candidate, RCV requires the voter to rank the candidates in order of preference. For example, in a 5 candidate race, there would be five spots to rank the candidates in.

In the first round, each candidate is ranked on how many first place votes they received. If they have over 50% of the first place votes, that candidate wins outright (similar to first-past-the-post). However, if no candidate has that, then the candidate with the least amount of first place votes is eliminated, and the ballots that had that candidate ranked first now get counted to whoever they had ranked as their second preference. This process continues until a candidate has over 50% of the voters’ preferences supporting them.

For a clearer graphic explanation, the city of Fort Collins, Colorado, has a great video example. But the Democratic primary for the New York mayoral race gave a real-life example of why RCV is gaining steam.

One of the more interesting aspects of the NY mayoral race was that it allowed for a broader range of candidates. Normally, in American elections, there is an effect called the “spoiler effect”. When an outside candidate enters a two-person race, they draw voters away from the candidate with the most similar views. Often, that leads to the last candidate, who didn’t have their votes siphoned, winning, with the outside candidate having “spoiled” both their chances and the similar candidate’s chances of winning.

This has led to tactical voting in the U.S. where voters often back who has the best chance to win and to prevent a specific candidate from winning. As a result, outside parties and candidates often have an incredibly hard time winning elections because they aren’t seen as viable AND they would siphon support from a candidate who has a better chance to beat the worst-case candidate.

The NY mayoral race tempered this effect with RCV allowing voters to have a 1st preference of a candidate who isn’t mainstream, while allowing them to then have backup preferences to dilute tactical voting. With this freedom to choose, New Yorkers saw candidates ranging from the democratic socialist Zohran Mamdani and pro-labor progressive Jessica Ramos to moderates like Michael Blake and pro-charter school investor Whitney Tilson.

RCV also allowed each candidate to focus on specific issues more intensely, whether that be specifically tackling homelessness, affordability, or early childhood education, which has served to make policies regarding those issues more thought-out and solid, as the candidates have to run a campaign based heavily on that platform.

There’s another positive outcome from embracing RCV; cordial and amicable campaigns. As mentioned before, having a list of preferences allows voters more freedom to choose, but it also allows campaigns room to bypass the (unfortunately) common practice of attacking their fellow candidates.

If two candidates have very similar policies, like Brad Landers, Michael Blake, and Zohran Mamdani did, they can acknowledge that they agree on many things and even go so far as cross-endorsing each other. It effectively tells voters, “we like each other a lot, and if one of us isn’t likely to win as the votes get tallied, put this other candidate next so that we can still tackle the issues we agree on”.

Save for Andrew Cuomo, who was attacked from all sides in a debate, the campaigns in the mayoral race had far more upbeat and policy-forward atmospheres, which stands in stark contrast to the presidential elections over the past few cycles.

All of this, between a wide range of candidates, policy-forward campaigns, and amicable campaigns, has come together to showcase one final aspect of RCV that the NY mayoral race revealed: it got younger voters out to the ballot box.

For the first time in recent memory, 25- to 34-year-olds turned out in the highest numbers, with 21% of the total votes and voters under 40 represented 40%. Additionally, there was a significant jump in first-time voters this year. With disillusionment in politics pervasive, especially among young people, RCV gave them a way to find a candidate who aligns with their values while also having an actual chance of winning. These candidates often fall outside of traditional Democrat or Republican circles, and it seems more freedom of choice has led to more civic engagement.

However, there are short-comings of RCV that are important to note.

For starters, the number of candidates and complexity of voting (relative to filling in just one bubble normally) can be confusing for voters while also making mistakes in filling out ballots more common, leading to those ballots being discounted. Another factor is that multiple rounds of ballot tallying takes longer and is more expensive, and it has raised concerns of transparency between rounds.

But even with these downsides, RCV is beginning to spread across the country. Nine states, beginning with Maine in 2018, already use RCV, although six only use it for the military and citizens living overseas. It’s also used in local and city elections in another 17 states with more states considering legislation to adopt RCV including Washington D.C.

On the flip side, 13 states have banned RCV in local elections, and the current political juggernauts will likely be disinclined to pursue it on account of it diluting their power and influence towards smaller parties. But with the momentum growing, it seems unlikely that RCV won’t continue to spread at the local and state levels.

Engagement Resources

- FairVote is a nonprofit organization that is a proponent of both RCV and the Fair Representation Act.

- Fair Elections Center is a litigation and election policy nonprofit who keeps a database of legislation related to elections

- Many states, including Maine and Virginia, have FAQ’s regarding their RCV policies in order to help voters and legislators understand the voting system.