Elections & Politics Brief #193 | By Inijah Quadri | August 24, 2025

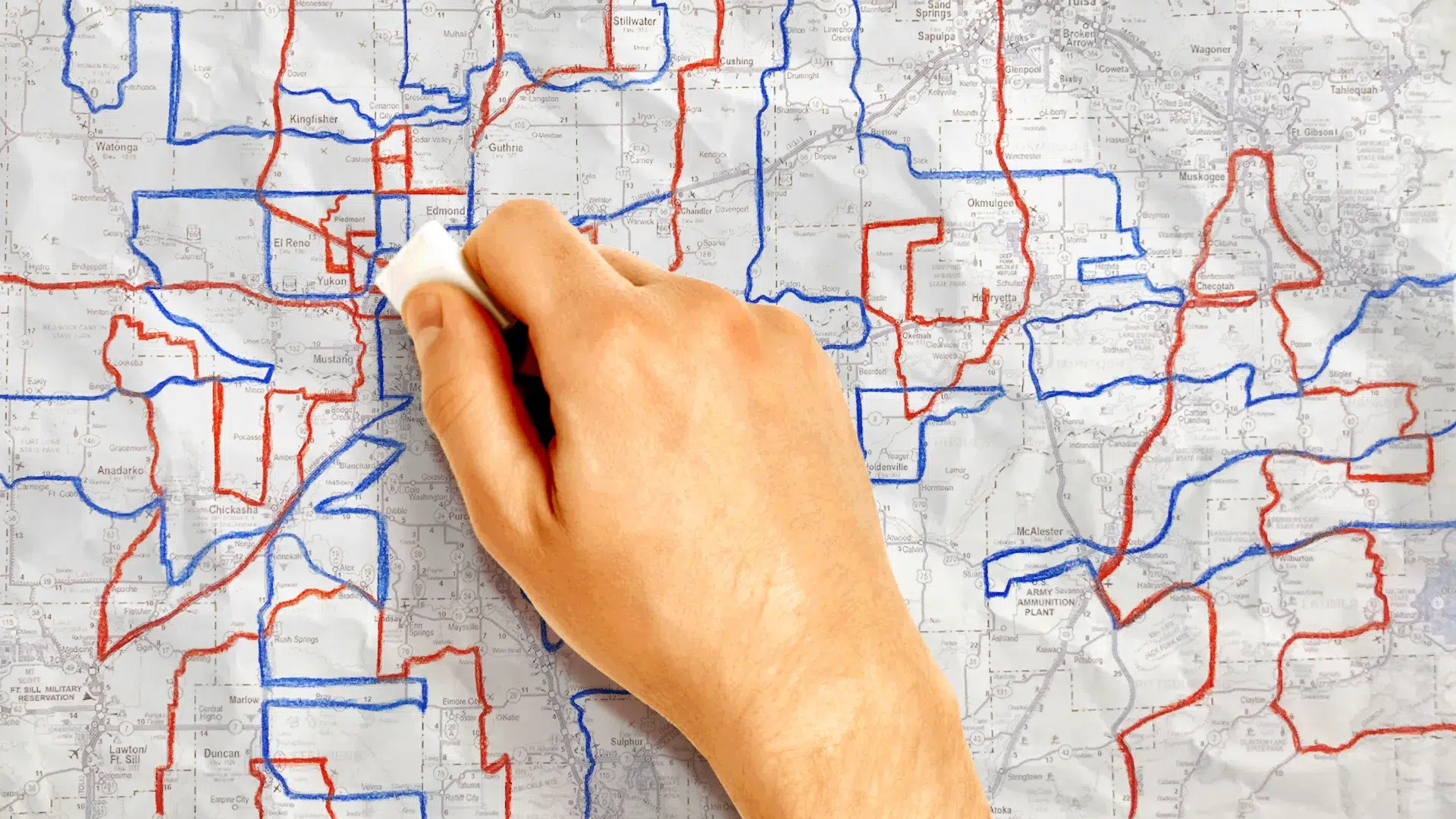

Gerrymandering began as a nineteenth-century power play in Massachusetts, when Governor Elbridge Gerry signed a state senate redistricting bill whose oddly shaped Essex County district reminded a newspaper illustrator of a salamander. The nickname stuck, and so did the tactic: drawing electoral district lines to advantage a party or faction and to weaken cohesive communities of interest.

Under federal law, redistricting is tied to the decennial Census. The Census Bureau must deliver Public Law 94-171 (“PL 94-171”) redistricting data to states within a year of Census Day, and states use those data to draw districts. This linkage is set in 13 U.S.C. § 141(c) and the Census Redistricting Data Program.

Modern constitutional law supplies the baseline. In the 1960s, the Supreme Court made redistricting justiciable and required roughly equal populations in all Congressional Districts: Baker v. Carr opened the courthouse door, Wesberry v. Sanders required near-equal congressional districts, and Reynolds v. Sims applied “one person, one vote” to state legislatures.

Later rulings narrowed federal review of partisanship while keeping protections against racial vote dilution alive. In Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), the Court held that partisan-gerrymandering claims are “political questions” beyond federal courts—but left regulation to Congress and the states. At the same time, Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act remains enforceable; in Allen v. Milligan (2023) the Court affirmed that maps that dilute Black voters’ power can violate Section 2. Preclearance under Section 5, however, has been inoperative since Shelby County v. Holder (2013) invalidated the coverage formula.

The result is a patchwork in which power struggles play out state by state. Recent flashpoints include Wisconsin’s 2024 shift to less-biased state legislative maps via state-court litigation, Texas’s 2025 mid-decade congressional-map push, and an August 2025 Utah ruling ordering new congressional districts before 2026.

Analysis

Gerrymandering keeps happening because the system rewards it. Winner-take-all, single-member districts let mapmakers create safe seats. Off-the-shelf GIS and mapping tools (e.g., ArcGIS Redistricting, Maptitude for Redistricting), public platforms (Dave’s Redistricting App, DistrictBuilder), and research codes (GerryChain) make precise map-drawing—and auditing—far easier.

But what counts as an “extreme” map? Plans that are statistical outliers compared to large ensembles of neutrally generated maps, or that produce durable seat advantages disconnected from statewide vote share. Independent evaluators like Princeton’s Redistricting Report Card and PlanScore quantify these patterns. Detection alone, though, doesn’t fix them.

What does it mean when courts call partisan gerrymandering a “political question”? It means federal courts say there are no judicially manageable standards to decide such claims; the remedy lies with Congress or state law. The Supreme Court said federal courts won’t decide whether maps are unfairly partisan under the U.S. Constitution (Rucho v. Common Cause(2019)). But states can still ban or limit partisan gerrymandering in their own constitutions and have their state courts enforce those rules—and Congress can pass a national law setting redistricting standards, which federal courts could then enforce.

Race and party often overlap, letting mapmakers hide discrimination behind “partisanship.” Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act bars voting practices that result in minority voters having less opportunity than others to elect candidates of choice. Plaintiffs typically must satisfy the Gingles preconditions (a sufficiently large and compact minority community, political cohesion, and bloc voting by the majority that usually defeats the minority’s preferred candidates) (Thornburg v. Gingles (1986)). Recent Section 2 cases—like Allen v. Milligan—have opened more opportunities for Black voters, even as other decisions (e.g., Brnovich v. DNC (2021)) set stricter guideposts for vote-denial claims.

The best short-term backstop is in the states. Independent or citizen-led commissions, strong transparency, and clear redistricting criteria can check the worst abuses. Commissions are typically created by state constitutional amendment or statute—often via voter initiative (e.g., AZ 2000; CA 2008/2010; CO & MI 2018) or legislative referral (e.g., VA 2020). As of 2024–25, eleven states use commissions for congressional districts (Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Michigan, Montana, New Jersey, New York, Virginia, Washington). Wisconsin’s 2024 state-court process, while not a commission, shows how state law can move outcomes closer to voter preferences.

But state-by-state fixes produce uneven protection. A democracy worthy of the name needs national guardrails. Congress could ban partisan gerrymandering, restore preclearance with a modern coverage formula, and adopt clear criteria that protect communities of interest. Status check: The Freedom to Vote Act was introduced in the 118th Congress but did not become law; the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act has been introduced in the 119th Congress (H.R. 14, March 2025) and is pending in committee.

A bolder path looks beyond better lines under the same rules. Multi-member districts with ranked-choice voting (e.g., the Fair Representation Act) would convert “safe seats” into proportional, voter-driven representation; opening datasets/algorithms, expanding independent audits, and banning mid-decade remaps would make cartography a transparent public good. Ending “prison gerrymandering” by counting incarcerated people at their home address—an approach already adopted by numerous states—would stop quiet population shifts that dilute urban representation.

Bottom line: the most durable fix is independent, citizen-led redistricting commissions in every state, paired with clear, enforceable criteria.

Engagement Resources

- Brennan Center for Justice (www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/redistricting-litigation-roundup-0): Redistricting research, litigation tracker, and explainer series on the current cycle and reform options.

- All About Redistricting (redistricting.lls.edu/state/ohio/?cycle=2020&level=Congress&startdate=2022-03-02): State-by-state law, process guides, and case summaries for practitioners and advocates.

- Princeton Gerrymandering Project (gerrymander.princeton.edu/redistricting-report-card/): Redistricting Report Card and methods that link math and law; useful for map evaluation and public comment.

- Prison Policy Initiative / Prison Gerrymandering Project (prisonersofthecensus.org/): Campaigns, state lists, and how-tos to end prison-based gerrymandering.

- FairVote (fairvote.org/press/fair-representation-act-2025/): The Fair Representation Act and resources on multi-member districts with ranked-choice voting.